In August of 2007 I revisited Mycenae, an archaeological site in the north-eastern Peloponnese famous for the instrumental role its incumbent Agamemnon played in the Trojan War, a mythological tussle which records the first ever instance the Greeks successfully banded together for the sake of a greater cause. Like a great many other ancient ruins in Greece, the Mycenae of today isn’t much to look at; save for the empty Treasury of Atreus, its hive-shaped tholos tombs, and some dilapidated fortifications, the legendary city has been stripped of its glorious structures and embellishments. Hence to experience the magnetism of the past one must invariably resort to a random exercise in active imagination, one which my companion and I tried from the palatial foundations which offer panoramic views of the Argolid and Saronic Gulfs.

When Heinrich Schliemann excavated the Late Bronze settlement at Mycenae, he discerned that the entrance to the citadel was by means of a ten by ten feet wide stone gate, called the Lion Gate for the sole reason that the carved triangular relief atop the structure depicted a Minoan pillar flanked by two fearsome lions. Save for their symbolic act of guarding the royal house, the wild animals appear to be venerating something that once stood atop the pillar and capped the ornamental design. Logically, there can be no way of knowing what stood at the pinnacle of the carved triangular slab, and an educated conjecture based on artefacts exhibiting homologous features may be the closest we’ll ever get to the truth.

The entire motif is recapitulated on a ceremonial seal found in the rubble of Cnossos, the largest and most important of the Minoan temple-palaces on Crete. Dating to about c.1500 bce, the seal vividly portrays the magic mountain of the world, the primordial mound of chaos, from which the Great Mother Goddess sprouts holding what appears to be a wand or sceptre. Directly behind her, a table stacked with an array of bull horns alludes to her identification with the luminescence of the moon, and specifically with the lunar phases which mediate the seasons, the ocean tides, the menstrual cycle and other earthbound forces. Thus, she is the fecund energies, the fruitfulness of the Earth. She is flanked by two lions, an animal which stands at the pinnacle of the animal kingdom’s pecking order as the ultimate apex predator. With their forepaws on the mountain, the lions venerate, protect and salute their Mistress. Watching from a distance is a Minoan youth, a young man, who shields his eyes from the blinding luminosity emanating from her presence.

As a syncretised whole, the image alludes to the emotionally coloured state of Great Mother worship, a time when the collective ego of humanity was beginning to differentiate or achieve a small degree of autonomy from a collective unconscious state known as uroboric wholeness. In actual fact, the vigorous psychic exchange with the collective unconscious would have greatly restricted the development of personality or individuality, and it would not be a hyperbole to say that human beings of matri-local cultures would have replicated the psychosocial patterns which govern bee culture or operated in quite the same manner that the sea nymphs or vampires did in classical mythology; as a wholly integrated tribal unit whose common aims and concerns were mediated and controlled by a matriarch, a high priestess who could draw to herself and appropriate the energies of the Great Mother Goddess herself.

The monotheistic goddess is, amongst other things, the epitome of love, and as an all-pervading numinous life force that animates created matter, she is the self-love that gives birth to humanity, to the lower beasts of the heavenly and earthly zodiac, to the plants, trees and stones, as well as the inhabitants of the underworld from the dark cavernous recesses of her womb before subjecting her creations to the cosmic cycles of time, itself embodied by the triune phases of the lunar satellite. Time also implies change, and change weaves together the strings of destiny. On these strings, she plucks tunes that transmute past into future, sperm and egg into foetus, seed into plant, flower into apple, spring into summer and water into steam, always varying the pitch and rhythm as to forge a plethora of marked differences between analogous events and homologous pairings. Thus, as the prime mover of this cycle, which measures the eternity of time but is in no way subject to it, the Great Mother Goddess is the creatrix of wisdom and war, life and death, chance and destiny, as well as prophecy and all forms of extrasensory perception; as its progenitor she stands at the primordial time origin of the cosmos, held aloft on her throne by the mightiest of the terrestrial beasts, the bull and the lion.

When it comes to telling the story of an ancient culture, or any culture in fact, giving an accurate measure of its cosmology and how its people may have thought depends on a systematic examination of its archaeological remains, particularly the omnipresent rites, myths and symbols. Myths are especially important, seeing that the narrative and story-telling process has revealed to us, time and time again, its intrinsic propensity to reshape and recast the cosmic clay which forms the mould of knowledge, the cultural attitudes, behaviours, and values of any society, as well as any political ramifications that may ensue as a result. We might compare mythological discourse to a thermometer which measures and reflects the increment and nature of our collective consciousness at any one time, a rudimentary process which acts as a necessary precursor to an evolutionary leap in critical thinking, inquiry and the way we process and evaluate information as a whole. While the manner of transmission is usually oral, the survival of individual pieces of myth-making across generations has always been precariously hinged on the written word, and, to a greater extent, whether or not the administrative leaders and their scribes decreed them worthy of transcription onto clay tablets, papyri or paper.

Herein lays the problem with Minoan cosmology. There are no surviving myths or fragments thereof that could contribute to a somewhat objectified representation of the cultural canon, or the central Great Mother archetype of the Minoan peoples. The cycle of myths which mention the story of the Athenian hero Theseus and his venture to the Cnossian labyrinth to save fourteen Athenian youths from the dreaded jaws of the minotaur is a latter fabrication, a classical piece of myth-making transmitted by the war-loving patriarchs of Mycenae who actively sought to recapitulate the subjugation of the Minoan temple-palaces through allegory and hasten the demythologization of its Mother Goddess. To add to the virtual absence of myth is the lamentable silence of the written scripts which has plagued– and continues to plague–the archaeological establishment. While it is true that the Linear B script was unveiled by Michael Ventris in 1952 to be an early form of Mycenaean Greek, the language is not a viable exponent of Minoan culture seeing that its inauguration occurred after the Mycenaean incursion of Crete. Further, its confinement to the administrative order of the temple-palaces and the inability to give voice to the religious and metaphysical concerns of the people as a result, further limits its cosmographical scope. The two scripts which will most likely shed light upon the earlier periods of Cretan cultural history, the mysterious Cretan hieroglyphic and Linear A, are yet to be deciphered. With this graveyard silence of written records and mythologems, our studies of Minoan culture depend heavily, if not entirely, on the universal languages of archaeoastronomy and psychology, as well as the vibrant intonations of visual art.

We know that the man generally credited for the discovery of the Bronze Age ruins of Cnossos at Kephala Hill in Crete is the wealthy Englishman Sir Arthur Evans ((1851-1941 ce), though it appears that the idea to dig there may have originated with someone else. In 1871, German amateur archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann made a name for himself through a heartfelt conviction that mythological treatises like the Homer’s Iliad and Virgil’s Aeneid wove real places and events into their narratives. Seeing that they recapitulated the Bronze Age world, the mythologems themselves contained clues of where significant Bronze Age ruins might lie in and around the Aegean. Schliemann’s eternal obsession with classical Greece and with the pugnacious heroes of the Trojan War eventually culminated in the successful excavation of historical Troy, Mycenae and Tiryns, and it appears that he had already devised plans to follow the mythological thread that lead to the mound at Kephala Hill before he was brought to a halt by the most feared of ancient enemies, death itself.

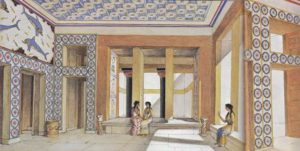

Following in the footsteps of his contemporary, Arthur Evans purchased the mound at Kephala Hill after learning that a local merchant had unearthed ancient earthenware in the vicinity. Accompanied by an entourage of indigenous Cretans, he began digging in March of 1899 and piecing together remnants of the island’s Bronze Age civilisation as if they were miniscule parts of a wooden jigsaw puzzle. In all certainty, Evans was probably expecting to find a primitive settlement composed of a few cobblestone streets, single-storey houses with fundamental amenities, simple utensils and so forth; instead, he ran into a highly sophisticated three and four-storey temple-palace comprised of narrow labyrinthine passages, architectural features like peer-and-door partitioning, flushed sewers and underground clay pipes that supplied rooms with hot and cold running water. The walls themselves were decorated with beautiful frescoes showcasing dolphins, flowers, griffins, and ritualistic activities like bull-grappling– all of which were painted in celestial blues, rusty reds and golden yellows, colours which emphasised the primary and harmonious communion between all creatures, tame or wild. In amongst the asymmetrical passages and rooms were gargantuan stone vats and pottery with double-axes, bucrania and geometrical motifs inscribed onto them, as well as gold or crystal signet rings and other jewels with depictions of bees, butterflies and anthropomorphic goddesses with upraised hands in gestures of epiphany. Other common themes included trees, lions, bulls and wheat, all images borrowed directly from Nature herself. Ubiquitous to the Minoan culture were the bucrania, also known as the Horns of Consecration, and the labrys, the double-headed axe. These entombed the mysteries of the Great Mother Goddess in their purest and original form for in the logic of primitive matriarchy the sacrifice of the bull with the labrys harnessed the combined energies of both the earth and the heavens, energies that renewed the eternal cosmic cycles. As sacrosanct implements, both were foremost of the paraphernalia used in procession during religious ceremonies and feasts.

At this point it would be wise to make the distinction between the archetypal and historical image or some other abstraction in visual art. The manner whereby we discern that the image is of the former is to look for it in cultures contemporary with the Minoan. In fact, we only need to travel across the Libyan Sea to Egypt to see that the guise of the Great Mother Goddess, expressed in her manifestation as bee, butterfly and griffin, as well as her consort and son-lover in the bull, is not exclusive to the Bronze Age civilization that thrived on Crete. There, the heavenly sky goddesses Hathor and Nut sometimes took the form of cows whose outstretched limbs straddled the four cardinal points of the earth. Hathor’s headdress of cow horns and lunar disc implied an astronomic connection; she was the bovine mother of the celestial bodies. Hence, if the primordial mother was imagined to be a cow, then the males of the progeny must without a doubt be bulls or bison. In fact, the god Osiris, whose cult appears to have originated in the Upper Egyptian town of Busiris and then spread to encompass the whole of Egypt, was often depicted as a bull. As the earthly incarnation of the god, the animal was worshipped at three major cult centres in Egypt; the Apis bull in Memphis, the Mnevis bull in Heliopolis, and the Buchis bull in Hermonthis. Further to the east, in Hindustan, the goddess Parvati arose from the primordial waters in the guise of a white cow. Being able to trace the homologous nature of these images across three distinct cultures no doubt entertains the idea that they are emotionally colored symbols that exist in the archetypal psyche of humanity, an avenue of logic that this study will dare to expound upon. Moreover, their implied astronomical origin introduces an obvious historical context, the idea that these icons found expression at a particular point in time.