Ironically, one can spend an entire life inveigled by dreary eyes and sightless slumber, ceaselessly hunting for ‘the medicine that hath more virtues then all the medicines of the earth’ without ever once being wantonly interrupted by the revelation that the answer to the mind-boggling paradox might be bequeathed by one’s own predecessors. Many moons ago, I, too, was content in looking for universal panaceas and miraculous medicines likely to confer longevity in sensationalized medical articles about the latest therapeutic techniques available; recombinant DNA research seeking to identify and expunge the ageing gene from the human genome; and an armamentarium of ‘magic’ and ‘happy’ pills gone viral. I looked for eternity and bliss along with the splendour and density of pure gold in the emptiness of intergalactic space and sought imminent transmutation within the inert forces holding rocks, shingle, and the geological strata of the earth together.

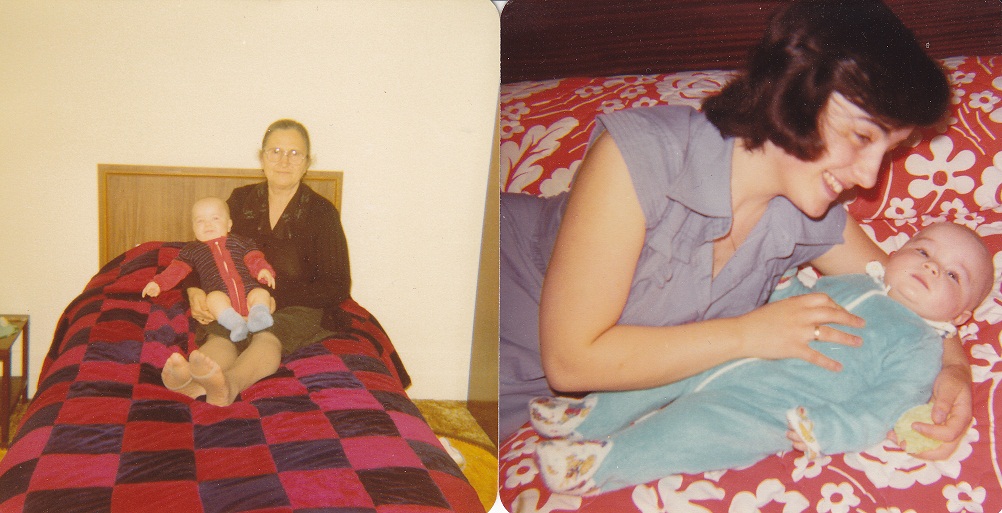

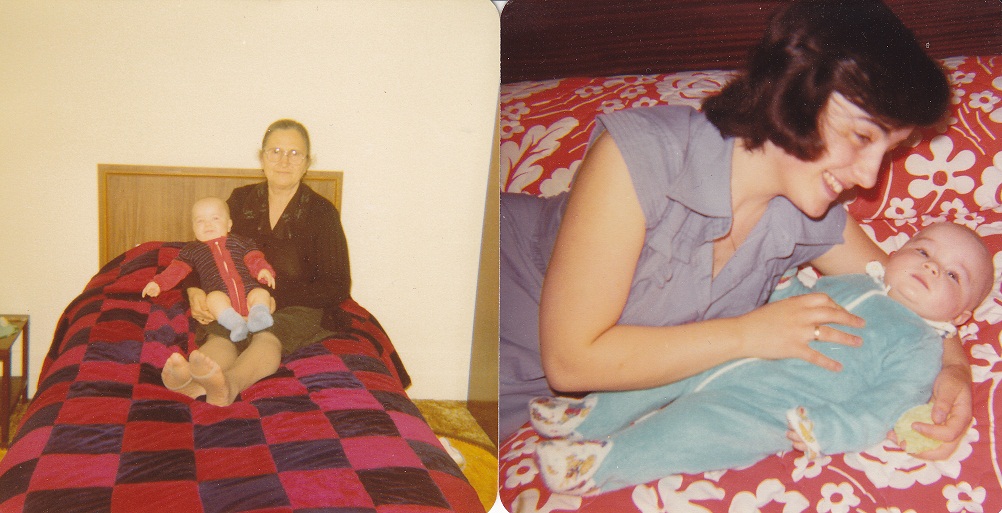

In a sense, I was too outwardly focused to understand that some conundrums of life are rendered much more comprehensible and subject to decipherment when one bothers to look inward. By looking inward, we juxtapose the physical and psychological foliated earth of which we are independently made against a consensual world in which we subjectively partake and have our being. This theory is avidly supported by the philosophical musings of the perspicacious classical philosophers who have adamantly claimed that the best possible way to study the phenomenology of human experience is through personal experience. And the objectified validity of personal experience is almost always amplified when it harmoniously espouses and builds upon anecdotal evidence passed down from previous generations; from our parents, our grandparents, our great-grandparents, and so forth.

Our consumerist and fast-paced society has spawned a whole generation of superficially-minded and ignorant individuals who are more than contented to live off processed and canned foods full of artificial colours, flavours, and preservatives. There are many reasons why people might make this poor and unhealthy choice of lifestyle: some are limited financially and cannot afford produce commonly dearer in price like free-range eggs, free-range chicken, and certain vitamin and protein supplements; some are hampered by busy schedules that resemble the flight timetables of JFK International Airport and don’t have the liberty requisite for the purchasing of ingredients and home preparation of healthy meals; and the rest probably don’t care enough about their own health to make any concerted conscious effort in purchasing and consuming nourishing and nutritive food. An unsolicited by-product of this trend is that there has been an upward surge in the incidences of obesity, cancers, heart attacks, and other serious health complications that sparsely perturbed the generations preceding ours. Moreover, those long-forgotten times seem to have begot many robust pastoral centenarians who infrequently fell ill and never sought medical attention when they did.

The obvious question begging to be answered here is why this deplorable turn of events should this be happening in an era when modern medicine has continued its ascent towards the peaks of mortal immortality in the treatment of complex ailments and conditions? Why should it be happening at a time when medicine shuffles nearer and nearer towards a cure for that merciless and dreaded slayer of humans called cancer? What has changed since the times of persons who thrived before the advent of contemporary medicine?

As I so pertinently discovered on one cheerful Saturday afternoon, there is a little treasure trove of knowledge waiting to be garnered about longevity for all those inquisitive psychonauts courageous enough to take the plunge and plummet into the cavernous depths of their own ancestry to see what there is flourishing. The substrate of genetic composition, as we all know, plays a fundamental role in one’s propensity to reach an advanced age; the right combination of genes can prove to be the vital difference between touching upon or penetrating the seldom visited terrain of triple digits and falling way short of it. Nonetheless all current research and anecdotal evidence implicate mode and style of living to be more consequential than genetic constitution.

On the whole, it appears that a few scant voluntary or involuntary choices in choice of diet might be the difference between dying at fifty and dying at a ripe old age of a hundred ….

*

It was late in the afternoon when I descended the flight of stairs leading to her room. I stood by the door for a few seconds, contemplating whether or not I should disturb a ninety-three year old woman from her daytime slumber. Was she still sleeping? I held my breath, thinking that even the slightest sound might zap her from that imaginal world of dreams where the elderly frequently withdrew to escape throbbing pains and debilitating physical weaknesses stimulated by their time-worn bodies.

I pressed my ear against the door. There were familiar sounds coming from inside: a news reporter based in Athens was relaying the latest developments on the political turmoil in Greece and the radio was broadcasting traditional Greek folk dances from western Thrace, her place of birth.

“Is someone there?” asked a soft but overtly familiar voice.

“It’s just me grandma,” I said, pushing the door ajar and stepping into the room. “I thought I’d pop down and visit.”

“Ah!” she exclaimed. “It’s my Paul.”

“Just me,” I said, smiling sheepishly at her. I could see that she was reclined on her single bed with her feet tucked beneath a green blanket. “Thought I’d pay you a little visit.”

“I’m glad you did,” she said. “You have no idea how boring it can get when all you have are four walls to talk too all day.”

“Did Aunt Stella come by today?”

“Yes,” she said, hoisting herself up from the bed. “She brought some moussaka over.”

“Nice.”

“Would you like some dear?”

“I’m fine grandma, I just ate.”

“Let me take those clothes off the chair so that there’s room for you to sit.”

“No, no, don’t worry about it there’s room over here,” I said, motioning toward the rear end of her bed.

“I just thought you’d be more comfortable with the chair.”

“Here’s just fine,” I said, plonking myself beside her. “Do you remember when I used to dash into your room and crawl into your bed at some ungodly hour when I was little?”

“Do I ever,” she said. “You used to experience many night terrors when you were a little boy. You’d wake up screaming and then run into your parents’ room.”

“And then they’d send me to you,” I said.

“That’s right,” she cackled. “They wanted to be left alone.”

“They did.”

“But things always change,” she pointed out. “Now they want you around all the time, don’t they?”

“That’s true.”

“See how time changes things,” she said

“They do,” I said. “I think when you’ve been around long enough to see some of those changes you have a much greater appreciation for the miracle of life.”

She pondered my assessment for a few moments before adding, “You’re quite right. Do you know what Paul?”

“What grandma?”

“Sometimes I can’t quite believe that I’ve lived to be ninety-three years old.”

“Why do you say that?” I asked. “A lot of people live to that age and beyond to become centenarians.”

“A lot of people do,” she said, gesticulating wildly, “but not a widow who has lived the vast majority of her life plagued by health problems. I didn’t believe that I would ever make it past fifty, let alone survive until such an advanced age as ninety-three.”

“Fate bestowed upon you the elegant gift of longevity,” I said.

She took a deep breath, exhaling slowly. I could see that my declaration had hurled her back into the tumultuous torrent of time. She was no longer in the present or the now; she was reliving an entirely random chain of bucolic experiences that had fashioned her into the gleaming column of stability, spiritedness, and indestructibility that she was. Her hazel eyes looked sultry.

“What’s wrong grandma?”

“You know, if I didn’t have your auntie and your dad, I don’t think I would remember that I was actually married at one time.”

“You didn’t get enough time with him, did you?”

She shook her head gently from side to side, sighing. “We only got to spent three years together. Three fragmented years I should say, for during that time most of the men of our village were forced to band into militia and take to the mountains where they fought vehemently against the German-loving fascists.”

“It was one of the lowest periods in Greece’s history,” I said. “There’s nothing more counter-productive and disparaging to national ethos than civil war grandma.”

“That damned civil war left me widowed at twenty-three,” she said, “with an infant daughter and another child on the way.”

“My dad.”

“Your father never had the privilege of meeting his own father Paul,” she said, her voice quavering.

“Grandma would you attribute your longevity to any one specific thing?” I asked, trying my best to inconspicuously guide the conversation away from the emotionally upsetting subject.

“Indeed,” she said quite matter-of-factly. “I attribute it to my thirst for life. My two children were my treasures and gold and I had to live for them. I simply would not allow myself to die. I forbade my own death Paul. Do you understand that?”

“Absolutely,” I said. “You were a woman on a mission.”

“A rustic woman on a mission,” she corrected, “and even fate is powerless to change or hamper the mind of a rustic woman once she’s made it.”

“I don’t doubt that for one second,” I said. “Why didn’t you remarry grandma? Being a single mother in those days would have been awfully difficult.”

“Oh, the relatives tried to organize meetings with many handsome and clever bachelors,” she said, “but it never worked.”

“Why’s that?”

“Well, to be open and honest with you Paul I would have liked to have a man in my life for the support and security that he could bring to my household, but the thought of having another man hit and discipline my children completely mortified me. I couldn’t stomach it so I just went without.”

“You obviously sacrificed a lot for your children,” I said.

“It was so worth it,” she said. “I have two beautiful gems of which I am so proud.”

“They are very proud of you too grandma.”

“Not having a partner and being single can be a blessing in disguise my child.”

“How so?”

“You don’t have to listen to anyone’s bickering but your own. Your partner’s bickering can subtract years from your life Paul.”

We both laughed at that. I felt the numinosity of our ancestral connection when we engaged proactively in unearthing personal memories from our shared past and when we partook of little quirky jokes that made little sense to everybody else. That’s how I knew I was Sophie Kiritsis’s grandson.

“There’s a conviction circulating nowadays that people of our generation aren’t living as long as those of your generation,” I said. “What’s your opinion about that?”

“I don’t know my child,” she said. “You probably know a lot more about that than I do.”

“Do you think much of it has to do with your diet and lifestyle?” I asked. “Our generation seems to be living out of cans and processed foods whereas yours lived a much more natural lifestyle; one that was closer to Mother Nature and unencumbered by artificial methods used to manufacture the processed foods you find in the supermarkets today.”

“Possibly,” she said. “We didn’t have drugs like aspirin and panadol in the village and we only ever used natural remedies to alleviate symptoms of disease and bodily wounds. We followed a quite frugal and staple diet that changed only slightly according to what the land willingly conferred during any one season. We ate bread made from flour and oats, wheat, rice, and some dairy products like milk, cheese, eggs, and yoghurt. A number of vegetables like tomatoes, peppers, cucumbers, and green beans were grown and harvested only during the spring and summer months but we had the pleasure of eating corn cobs, onions, and pumpkins all year round. Fish, chicken, and pork we had occasionally. Other higher quality meats like beef were much scanter commodities. I only had one cow and couldn’t afford to sacrifice her.”

“The free-range chickens and eggs would have been so scrumptious.”

“They were,” she said. “I remember we had a few sophisticated women who eventually moved to Thessaloniki to pursue careers and every time they returned to the village during the summer months the first thing they always did was to knock on my door and ask me for free-range chicken and eggs.”

“That’s because the meats which they were consuming in the city were packed full of chemicals and had no taste,” I said.

“Yes,” she nodded.

“The build-up of all those negative vibrations and all that macabre psychic trauma inside battery farms wouldn’t do much for general taste either,” I said. “If anything, they would probably leave a sour taste in the mouth.”

“Yes,” she said. “In any case I had to closely watch what I ate because I had problems with my stomach. I frequently experienced nausea, vomiting, and stomach pains. It was usually quite manageable, but once every so often it would get so severe that I would keel over in pain. ”

“Ah yes, you’ve told me about this,” I said. “Must have been dreadful.”

“It started in my late twenties and basically defined what I could and couldn’t eat,” she said. “I had all my salads with sesame seed or olive oil and I could only eat boiled or grilled meat. Anything fried would awaken unpleasant sensations in the gut.”

“Mum’s grandfather who lived until ninety-nine also had problems with his stomach,” I said. “Mum says that he only ever ate grilled meat with salad. Do you think having a stomach problem is a blessing in disguise grandma?”

“How so?”

“You tell me,” I laughed. “It basically forces you to avoid fatty foods and other nasty little things that clog up arteries and veins and cause heart attacks. Your problem was secretly your saviour; your elixir of immortality.”

“It’s hardly an elixir of immortality my Paul,” she said. “Perhaps you meant an elixir of longevity?”

“That’s it!” I exclaimed. “You know what scientists say grandma?”

“What do they say my child?”

“If it’s only happened once it won’t ever happen again, but if it happens twice there’s probably a latent causality there well worth looking into.”

She smiled. “That’s a good point you make.”

“So what are the rest of the ingredients?” I asked.

“For what?”

“For the elixir of longevity,” I said. “I need the rest of the ingredients so that I can produce it in liquid potion form in my garage laboratory.”

She ogled me with a candid look of concern that only a loved one can give. “Paul, have you been getting up to mischief in the garage again?”

“I’m only joking,” I said. “What I meant by other ingredients was the configuration of your personality.”

“You know what your grandma is like,” she said.

“I don’t know what you were like when you were younger though,” I said.

“Oh Paul, people don’t change,” she said. “Does a leopard change its spots? Don’t let outward appearances fool you my child. Sometimes people like to give the impression that they’ve changed for the better but underneath the façade they’re still the same person. The personality inside this aged and fragile old woman living in Melbourne Australia today is the same personality as the vibrant and highly animated one who walked the streets of Ligaria village in northern Greece some sixty years ago.”

“Please elaborate,” I urged her.

“I’ve always been expressive, talkative, and very direct in my disposition,” she said. “I’ve always been a woman of truth and principle, one who wouldn’t and couldn’t tell a white lie to save the life of her own child. My father was stitched together of the same moral drapery and I loved him dearly. Like him, I always knew I could handle whatever life chose to throw at me.

I generally feel that the more you’re loved by God, the more you’ll end up suffering in life my Paul. That’s the philosophy that I’ve always adhered to for a piece of mind and for the sake of keeping tight reins on my own sanity. I have always been subject to stress and worry and yet I’ve always found effective ways of jettisoning it. You won’t live long if you fail to express your own being or if you fail to find a feasible outlet to let off emotional steam.

In hindsight I think there was one quality that contributed to my longevity more than any other.”

“What’s that grandma?” I asked.

“I accepted my fate,” she said. “I knew I couldn’t control the remorseless calamities that befell me in my early years, so I accepted the pain and bitterness.”

“That you did dear grandma.”

“I not only accepted the bitterness,” she said, “I gulped it down as if it was a delicious, sugar-coated loukoumi (Turkish delight).”

“Acceptance is closure and it eliminates severe stress, fear and other detrimental emotions,” I said. “I’m sure that’s played a role in your longevity.”

“Yes.”

“So too has your choice of diet,” I said. “Or lack thereof.”

“As I said, I didn’t have much of a choice when it came to food Paul,” she said. “I had to prepare and eat food in a way that wouldn’t disturb my stomach.”

“It wouldn’t seem like a choice to you,” I said, “but anyone able to rise above the circumstances of your life would see that your lifelong medical condition forced you into making a choice. It was a forced choice grandma. Forced choices and acceptance granted you an extended life so that you may enjoy the company of your children, your grandchildren, and your great grandchildren and share your wisdom and knowledge with them.”

“I guess so.”

“You are loved by God,” I said, winking at her. “Not many people can say that they’ve had the pleasure of meeting their great grandkids, can they now?”

*