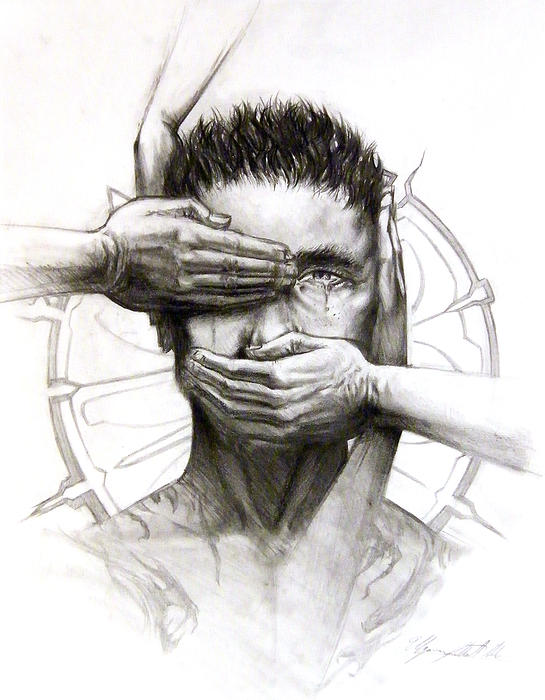

Many people are often surprised when they learn that the act of confessing is actually a therapeutic method, and an effective one at that. In turning to a significant other, perhaps a priest, confidant or just another human being and entrusting them with our innermost thoughts, secrets, and problems, we are in effect expelling the accumulation of psychological garbage and cleansing our inner beings. There are a great many cases, especially in indigenous cultures, where the confessional act actually saves an individual who has committed a social transgression from suffering illness or an acute psychogenic death. This is not imaginary; it is a documented fact recorded by many ethnologists and anthropologists who have spent much time studying indigenous medicine and healing methods.

Some of the most dramatic accounts of healing through confession come from Uganda, Central Africa, and Polynesia. Usually the onset of the illness is sudden and unprecedented. The victim might be perfectly healthy and happy one minute and then suddenly experience a reversal of temperament in which he or she becomes inert, inactive, unresponsive, lethargic, and short-tempered. According to many eyewitness reports made by Westerners the victim’s whole physiognomy changes so that his or her actions appear disordered and mechanical. Usually there will be distressing period preceding a sudden lapse into unconsciousness whereby all communication and nourishment is forsaken. Death follows quite rapidly if the victim does not seek a medicine man or physician for the sake of confessing. What we find amongst indigenous cultures where the belief in confession abounds is that the notion of “sin” or committing a “sin” as understood from a religious and dualistic perspective is one and the same with a “breach of taboo”.

The condition of transgressing is quite heterogeneous in nature and concrete laws or rules are non-existent. Hence a “sin” might be voluntary or involuntary and conscious or non-conscious. Breaking moral codes is also a projection of “sin”, as is protracted labour before childbirth, adultery, drunkenness, theft, verbal offences, and sterility. In developed areas of the world like the United States, Europe, and Australia where the monotheistic religion of Christianity reigns we tend to perceive confession as an act which transpires in complete privacy and under the mediation of a priest. Amongst autochthonous peoples the context is very different; the “sinner” will admit his or her sacrilege or wrongdoing publically before a shaman, medicine man, or healer attempts to purge it from the body through ordinary physiological procedures like forced vomiting, washing, and bleeding. From this inverted perspective the enterprise of “sin” that might be used in a modern sense as a descriptor of dirty laundry becomes a collective concern of the utmost importance. It is also worth mentioning here that a subjectified shame imposed onto an individual does acquire a life of its own and becomes as much of a reality to the transgressor as the menacing clouds in the sky or the mantic dreams experienced during sleep. If one adheres to the idiom of mind over matter then it shouldn’t come as any great surprise that a “sinner” who has not been expunged of their “sins” will inevitably fall ill and die.

One such case where the ancestral taboos were transgressed by a young boy was described by missionary Reverend Grebert whilst he was stationed in the former French Congo. According to Grebert the boy was suddenly overcome by violent paroxysms so powerful that they knocked him from his feet and choked him. Distressed onlookers were quick to offer an explanation: “He ate bananas that were cooked in a pot that had been used previously for manioc. Manioc is eki for him; his grandparents told him that if he ever ate any of it–even a tiny bit–he would die.” The logical explanation here is that the ancestral taboo or suggestion that decreed that one could die by eating manioc was so heavily ingrained in his subconscious that it manifested or “objectified” itself in the physical convulsions. Grebert explains that an antidote for such a condition existed. In fact, a member of the tribe had dashed over to a neighbouring village where it was readily available to collect it. Lamentably the whole enterprise terminated fatally because the asphyxia that had taken possession of the boy surmounted his weakened heart before the man could return. This tragic case might be explained as a psychic situation whereby a cultural suggestion, in this case a form of ancestral taboo, acquires a life of its own by penetrating the subconscious and then manifesting psychosomatically.

Our own conception of “sin” has been derived from the Semitic groups of the Orient and is ascribed a prominent position in the cosmology of the world’s three major monotheistic religions–Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In former times the word denoted a contravention of moral laws that were inextricably linked with the will and commandments of Yahweh, and mental or emotional illness was merely a by-product of “sin”. Many of us will identify strongly with this particular interpretation because it delineates the social and spiritual path our immediate ancestors have treaded along. Surprisingly these “Western” conceptions about “sin” do not contradict those that developed amongst other disparate cultures like the Aztecs of Mexico or the Incas of Peru. It just so happens that these Indian groups also emphasized the importance of confessing one’s “sins” to a religious pastor. The Incans actually ascribed certain dates as confessional where an individual could consult with the ichuris or priest of the clan and express contrition. Like many other racial groups illness was explicitly perceived as a consequence of wrongdoing and so the relatives of families nursing the sickly were urged to confess. In the case that the chief Inca himself became ill the entire tribe had to confess!

The idea of confessing to propitiate a higher intelligence or power and nullify a “sin” committed either consciously or unconsciously has definitely survived the test of time. It exists in a great number of existing religious traditions today where dualistic perspectives of the world and of being are maintained. For some congregational denominations of Christian religion like the Jehovah’s Witnesses the act of masturbation is a “sin”, as is abortion, pornography, lying, spiritism and esoteric dialogues of interfaith, drug abuse, gambling, homosexuality, polygamy, or the willingness to accept a blood transfusion to save one’s life. But for the vast majority of persons on this planet the evolution of modern science shifted the collective vision away from the subjectified dogma of personified cosmic powers towards a more “objective” dogma that emphasized the neutrality of all knowledge pertaining to reality. As children of this intellectual movement, both modern dynamic psychiatry and psychology have jettisoned the term “sin” for the more appropriate “guilt feeling”; the word “sin” is no longer appropriate in an progressive scientific worldview simply because it encompasses too many mantic associations with a god or gods that inhabit a celestial realm and controls human beings like little pawns on a chessboard.

Whichever cosmogony we choose to adhere to, whether that is primordial or modern and religious or scientific, one thing remains certain: confession encompasses a therapeutic value and can alleviate the physical and mental symptoms associated with disease. The question of how and why remains a subject of much enthusiasm and debate and will continue to be for some time yet. But the fact that it happens makes it nothing short of a miracle.

I, too, have confessed many times before. Some of my “sins” are transcribed in my book Fifty Confessions…