“There is no greater agony than bearing an untold story

inside you.” –Maya Angelou

Creative narrative and storytelling stands

at an evolutionary junction reflecting the gradual emergence of semantic

language, culture, and the social brain . They predate science, property rights,

. They predate science, property rights,

medicine, the consumer societies birthed by the Industrial Revolution, the

religious work ethic, and anything else of worth ever invented by the human

species. More importantly though, they allow for a constellation of individuals

with identical or analogous moral ideals, ethical standards, religious beliefs,

and cosmogonies to interweave, self-organize, and facilitate a context for personal

movement to self-actualization and henceforth serve as collective repositories

for the co-construction and transmission of culture. Desire for subsistence and

inherent meaning is a driving force to be reckoned with, and its sheer value

and aptitude in being able to relegate our perceived differences to the

wastebasket of triviality is reflected in the cross-cultural immanence of oral

and written myth in bygone civilizations and through Hollywood movies,

television serials, genre fiction, and pop magazines in the contemporary

developed world. At the very core of narrative gravity is self-identity (Dennett,

1991); it has occupied and continues to occupy so much subjective mental space

because it is the principal mechanism through which all generations have

recreated thyself. Without a doubt we

come to know conscious and unconscious aspects of the self (Snyder, 1998), our

competences and limitations, our motivations, and our aspirations through

narrative.

Save for reflecting the sociocultural

milieus and encompassing blueprints for behavior, identity, and theoretical

knowledge in all known cultures, narrative probably emerged, in part, as a

mechanism of neural integration and coordination between the dominant and

nondominant hemispheres of the brain (Cozolino, 2010). If this is indeed true,

then a multilevel function of narrative is to facilitate neural connectivity in

the brain, emotional stability, psychological flexibility, and psychosomatic

health. Dan Siegel has much to say about this curious phenomenon. The

integrative neural processes occurring during formative periods of development

occurring during formative periods of development

can be vertical, dorso-ventral, or interhemispheric (Siegel, 2012). The

importance of the latter, according to Trevarthen, cannot be overstated because

the anterior commissures and corpus callosum combined is, “the only pathway

through which the higher functions of perception and cognition, learning and

voluntary motor coordination can be unified (Siegel, 2012, pp. 341).”

Associational neurons in the frontal, temporal, and parietal lobes are the

modus operandi, linking intricate representational processes of the hemispheres

together (Cozolino, 2010).

Concerning the importance of narrative

in interhemispheric coordination, scientific treatises activate only the

digital, temporal processes of the dominant left hemisphere whereas the

combined visual imagery and linear storyline couched within real stories and

fictional tales activate both the aforementioned and the holistic, analogic

processes of the nondominant right hemisphere (Siegel, 2012). In light of this

interdisciplinary schema, it appears that our genetic and neurological

constitution come with in-built “attractions” for higher-order activities (i.e.

reading and listening to stories or creating them) able to activate and hence

or creating them) able to activate and hence

integrate cortical and subcortical processing systems, the hippocampus and

amygdala, and specific regions of the frontal lobes (Rossi, 1993). Moreover, creative

storytelling stimulates denser connectivity between the language centers; the neural

networks dedicated to memory, visceral, and emotional processing; and conscious

awareness (Cozolino, 2010). Albeit unconscious, there’s a reason as to why we

recourse to them when we’re suffering from self-perpetuated patterns of depression,

anxiety, over-emotionality, or a sense of emptiness and meaninglessness in our suboptimal

lives.

Let’s

attempt a substantiation of the abovementioned claim with some palpable

examples from my own personal experience. In the last eight months the rigorous

intellectual demands of gradual school inadvertently lead to the abandonment of

hitherto present artistic endeavours like creating writing, reading novels, writing

poetry, drawing, playing the keyboards, and doing jigsaw puzzles. Before I knew

it I was meandering inside the labyrinth of syllogistic reasoning, cause-effect

relationships, and interpretation, pumping out scholarly papers at an

astronomical rate. Although unconscious of it at first, the biases patterns of

left-right activation began cropping up in my subjective conscious experience

began cropping up in my subjective conscious experience

as irritation, agitation, and a slight nervousness. Some basic feelings of emptiness

and desolation associated with this lopsided life orientation were also present.

Something didn’t feel “right” anymore; there was something missing.

Unable to isolate and scrutinize these

at the time, I continued spiralling into a lamentable lapse of discontentment

until my very conscientious and astute psychotherapist reorientated me to the

inner world of images, symbols, and heroic journeys, the same plane the

storytelling process appropriates for the sake of recommencing dialogue between

the value-laden ego and the rich tapestry of archetypal content irrupting from

the unconscious (Snyder, 1997). Done in a context-appropriate manner, my

therapist’s solicitation to create self-narratives in a personal journal by

combining creative storytelling with the writing process occasioned in emancipation

from emotional arousal and stress and increased feelings of exuberance, contentment,

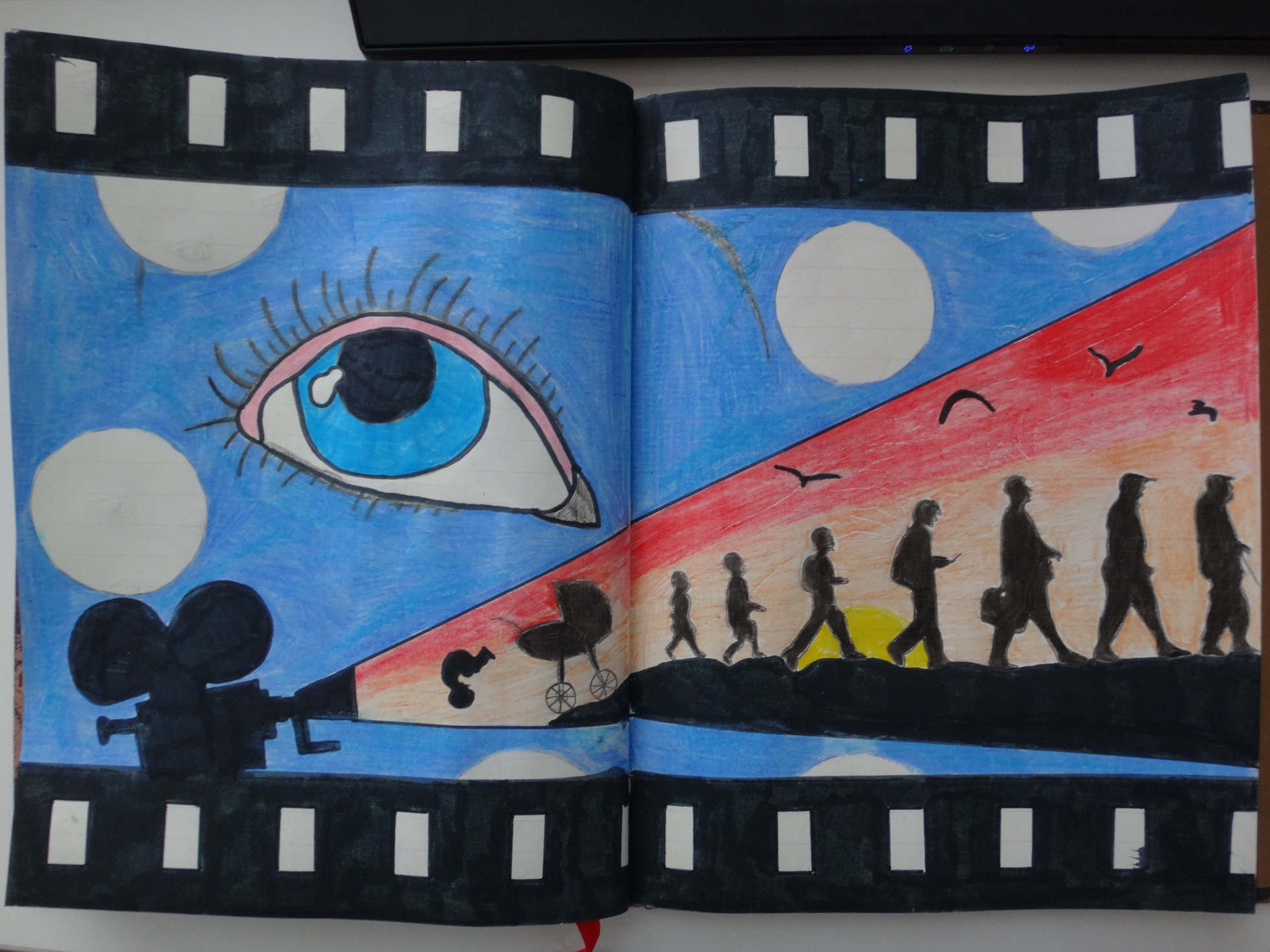

and wellbeing. This creative project evolved into something much more powerful

and profound during Expressive Arts Therapy class, examining existential,

spiritual, and metaphysical themes via the integration three different

modalities–drawing, poetry, and prose. Another more reductive mode of

expressing this would be to say that the creative processes unleashed led to a

readjustment of right-left balance .

.

On a similar note the consensus amongst

neuroscientists is that the corpus callosum, the bundle of nerve fibres interconnecting

and coordinating the two hemispheres, doesn’t reach full maturity until early

teenagehood (Galin, Johnstone, Nakell, & Herron, 1979). From about twelve

onwards, I became fascinated with genre fiction, especially drama, thriller,

and horror, petitioning my parents for books written by Richard Laymon, Dean

Koontz and Stephen King. Being firm believers in education and intellectual

and intellectual

stimulation, they complied with every request and so instead of engaging in

activities more pertinent to my age group (i.e. playing make-believe), I

devoured suspenseful and stimulating narratives from the opulent comfort of my

cerulean-tinted room. By the time I’d reached sixteen I’d read about a hundred

and fifty fiction books. Deliberating on the progression of my own development,

it recently occurred to me that this early passionate and sometimes

pathological fixation with the artificial worlds of genre fiction may have not

been a random epiphenomenon of innate curiosity per se, but a necessary

catalyst for enhanced metabolic activity and right-left neural integration.

A still deeper exploration of cerebral

pathways illuminates narrative and storytelling as the fundamental catalyst of neural integration. In circumstances where

an individual is relaxed and composed, affective processes mediated by dense bidirectional

connections between the orbitomedial prefrontal cortex, amygdala, anterior

cingulate, and right hemisphere are encumbered, manifesting as the direction of

focal awareness to stimuli of the external environment. This connotes increased

prosocial behavior and contentment, for the most part. Psychological stress, anxiety,

and negative affect are detrimental because they increase levels of cortisol in

the bloodstream, activating the amygdala’s fight-flight-or-freeze response which

leads to inhibition of the cortical networks (specifically the orbitomedial

cortex) regulating bottom-up survival processes like emotions, drives, impulses,

and so forth (Kern et al., 2008). When the amygdala is allowed to disrupt

homeostatic balance of emotional arousal and focal attention over sustained

periods of time, symptoms of depression and psychotic features may arise (Cozolino,

2010).

Gradually, the mutual effects of

antisocial behavior and atypical intrusions into conscious awareness from

deviant, invasive, and ego-dystonic voices breed fallacious interpretations

known as delusions which disconnect the individual from consensus reality. Now

our phylogenetic history shows that perceived detriments connected with impositions

of primary process thinking and implicit memory from the right hemisphere do

not outweigh the benefits, otherwise natural selection would have propelled it

the way of the dinosaurs some time ago. Whatever the reasons for evolutionary

retainment, the former permit direct access to archetypal contents and mythic

images from whence a more resilient contextual self may be wrought and a more goal-directed

movement to self-definition cognized (Snyder, 1997). More and more, it seems as

though narrative and creative storytelling activate a particular pattern of dynamic

unconscious processes able to yield all-powerful revelation from archetypal content

saturation in the subjective mental sphere, and reintegration of left-right

processing systems after their provisional dissociation in the more objective

neural sphere. Based on the aforesaid theoretical and experimental research, one

should surmise that narrative is an extremely compelling form of expressive

arts therapy and can be applied as an adjunct to a miscellaneous range of

clinical populations.

Creative storytelling and writing can

be applied to a wide array of clinical populations, including individuals

suffering from anxiety and depression, bipolar disorder, and psychosis

(Mehl-Madrona, 2010). Anxious and depressed people suffering from emotional

dysregulation would best benefit if we first identify their underlying

psychological trigger and then co-create a narrative that transforms the

perceived nature of the stressor from arbitrary and detrimental to essential

and temporary, imbuing the client’s life with richness, empowerment, and

meaning. For a depressed parent who has lost her only child, for instance, we

might suggest co-creation of a memorial project binding together the latter’s stories,

milestones, and interests into a personal myth that places an otherwise

nonsensical participatory event into a meaningful context. Similarly, a bipolar

sufferer who is demotivated and depressed and won’t leave the house can be

inspired with the co-creation of narratives whereby the detrimental voices and

characters pervading the inner world can be made conscious, dialogued with, and

transformed into less maladaptive, irrational, and self-defeating ones. On the

other hand a psychotic self can build meaningful stories around its aberrant,

disturbing, and ego-dystonic experiences for how to better function in

consensus reality. A belief that aliens are inserting microchips into one’s

cerebral cortex or that aliens have bugged one’s house might be therapeutically

countered through the active co-creation of stories in which aliens have either

become trapped in another dimension or forgotten how to reach Planet Earth.

Perhaps the most important ethical

consideration when applying creative storytelling in psychotherapy is the

characterological disposition of the client herself. One cannot truly benefit

from creative-oriented endeavors when self-perception is riddled by serious

doubt and uncertainty surrounding the ability to deploy imagination, to

actively create and recreate in the service of valuated action and goal

attainment, and to express the landscapes of the inner world. Some individuals

just aren’t open to working with the imaginal plane. Another caveat for the

expressive arts therapist concerns the client’s familiarity with the approach

itself; individuals schooled in the arts, particularly in creating fiction, may

really struggle with spontaneous expression because entrenched deep in their

cognitive machinery is the belief that the emergent creative product must

adhere to learned techniques and conventions. As we know setting concrete rules

and boundaries encumbers the teleological propensities of process work. Hence

the modality may not be nearly as effective when it constitutes one’s

profession.

In cases where narrative is a

co-creation between the therapist and client, the former should always be

mindful of the latter’s participatory level with mythological, folkloristic,

and idiosyncratic aspects of their own culture. Therapy can go a little awry,

resulting in annihilation of the dyadic container of safety and trust if the

therapist unwittingly recourses to certain symbols, images, and leitmotifs which

are taboo and carry negative intimations and undertones. Similarly, the

therapist should remain ‘sensitized’ to contextual information because the

unconscious irruptions facilitated through these techniques may in fact be

proto-scripts for premeditated actions like suicide attempts, homicide, and

other malicious behaviors. There’s nothing more lamentable than feeding the

fantasies of a criminal or psychopath with homicidal impulses. Over and above

all, the approach must be self-directed, meaning that it must somehow be

congruent with the client’s own needs and objectives as they stand in the

present moment. Phenomenological experience seems to be the best yardstick in

ascertaining whether or not creative storytelling is a viable medium for

personal transformation; therapists know they’re on the right path when their

clients utilize the imaginative process to actively and fluently connect with

hitherto untapped aspects of their own selves in reparative ways.

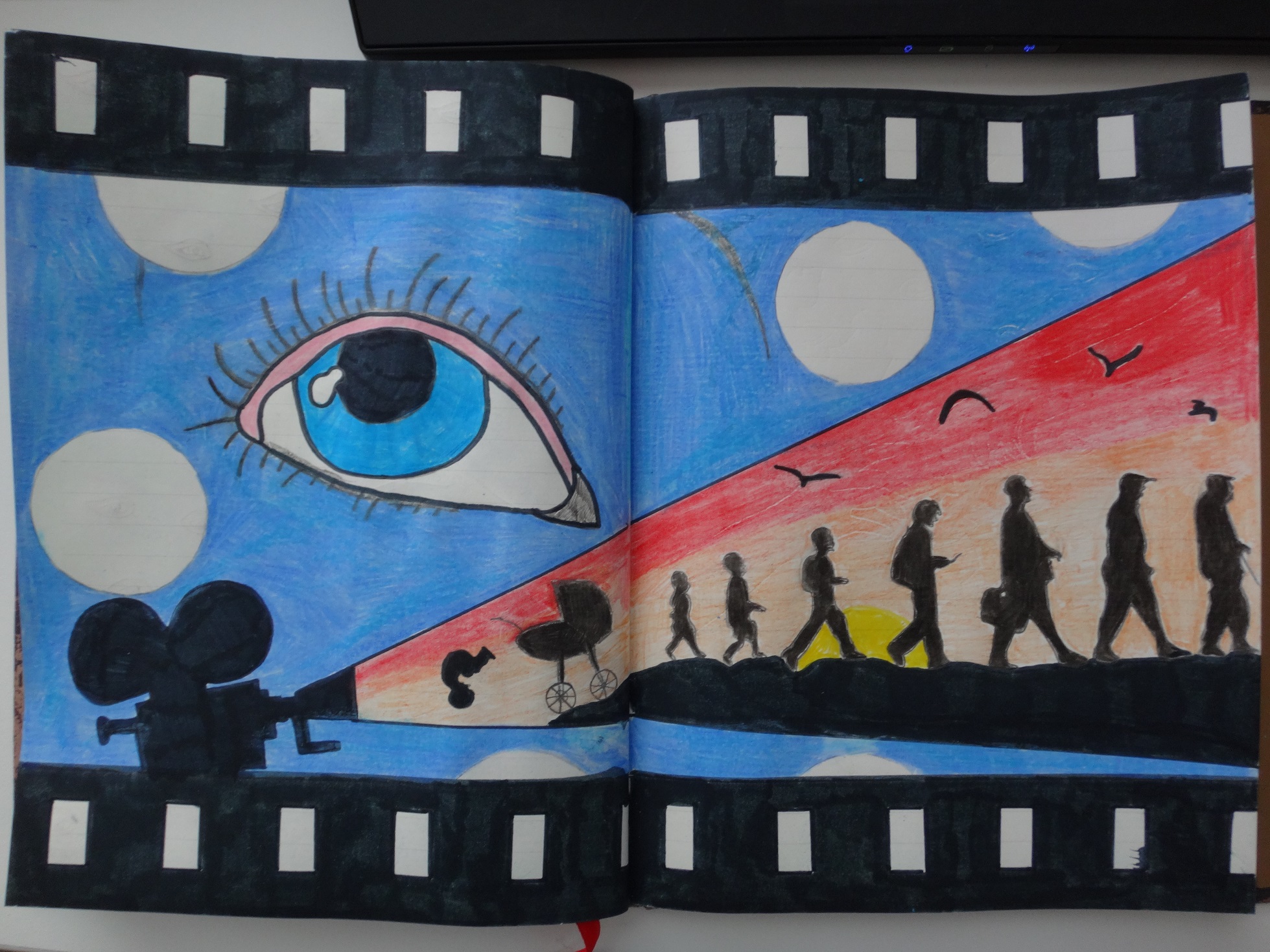

On reflection creative storytelling is

a universal phenomenon, transcending epoch, place, sex, religious and spiritual

orientation, and sociocultural milieu. Long before the emergence of semantic

language, our ancestors congregated about fireplaces to listen to engaging

narratives about mass migration, the far-reaching consequences of the world

flood, and the seemingly insurmountable quest of a heroic ancestor to undermine

the forces of evil. Their pre-eminence in our phylogenetic history is

explicable within both cultural and neural contexts: they contribute to the

co-construction and transmission of culture from generation to generation

whilst concurrently fashioning and maintaining sophisticated integration of

left-right hemisphere and cortical-subcortical neural circuitry (Rossi, 1993). Narratives

ground our experience in ways that allow for goal-directed action and

progression to self-definition; they link our individual selves into a group

mind like beaded pearls of a beautiful necklace; and they support the

complexity and self-organization of brain function.

Because the therapeutic and cathartic

qualities of creative narrative are neither arcane nor empirically sketchy, a psychotherapist

who deems themselves competent, conscientious, and versatile would do well to

apply them in the treatment of numerous clinical populations including the

anxious and depressed, the manic depressive, and the psychotic. Certainly there

are important caveats to be heeded when one meanders along that path.

Therapists troubled by the question of whether to ‘story or not to story’

should look to the phenomenology of experience for their answer: a client’s receptivity

to the imaginal world and willingness to create proactively in the service of

self-definition and personal identity are two of the best measures in

determining whether the approach will be efficacious or not. We are more than just

a bundle of psychobiological compulsions strung together by habit, we are our

therapeutic narratives. Nonetheless, we must own and become them if we are to

heal.

Bibliography

Cozolino,

L. (2010). The Neuroscience of

psychotherapy: Healing the social brain (Norton Series on Interpersonal

Neurobiology). WW Norton & Company.

Dennett,

D. C.(1991) Consciousness explained.

Boston: Little, Brown.

Galin,

D., Johnstone, J., Nakell, L., & Herron, J. (1979). Development of the

capacity for tactile information transfer between hemispheres in normal

children. Science, 204(4399), 1330-1332.

Kern, S., Oakes, T. R., Stone, C. K., McAuliff,

E. M., Kirschbaum, C., & Davidson, R. J. (2008). Glucose metabolic changes

in the prefrontal cortex are associated with HPA axis response to a

psychosocial stressor. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 33(4), 517-529.

Mehl-Madrona, L. (2010). Healing the mind through the power

of story: the promise of narrative psychiatry. Inner Traditions/Bear &

Co.

Rossi, E. L. (1993). The psychobiology of mind-body

healing: New concepts of therapeutic hypnosis. WW Norton & Company.

Siegel, D. J. (2012). The developing mind: How

relationships and the brain interact to shape who we are. Guilford Press.