Roberto Assagioli is best known for his practical application of transpersonal philosophy to psychotherapeutic methodology. As a product of upper-middle-class Venetian life, Roberto was exposed to the kind of cultural nexus that facilitates much more holistic views of psychology than ones afforded by Darwinian variants (behaviourism and psychoanalysis) at the time. Roberto’s’s adopted father, Dr Emanuele Assagioli, avidly supported his ambition to become a psychiatrist and in 1904 the family relocated to Florence so that he could commence preliminary training at the Istituto di Studi Superiori and further still engage actively with literary and philosophical circles whose elite members would later become his intellectual peers. The internship enabled an enviable path that culminated with medical supervision under the gargantuan wing of Bleuler in Switzerland; an intense fascination with the philosophy of psychology taught by William James; and a cordial meeting with Carl Jung (1875-1961), a Swiss psychotherapist whose theoretical suppositions and practices were comparable to his own.

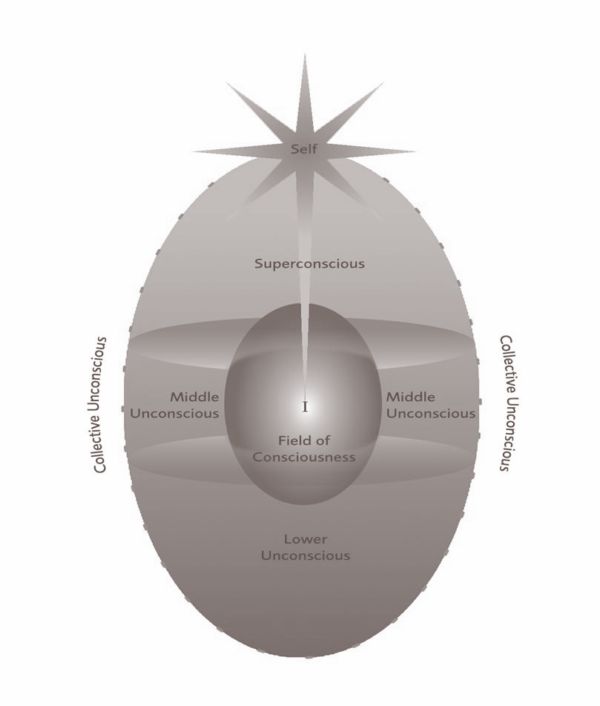

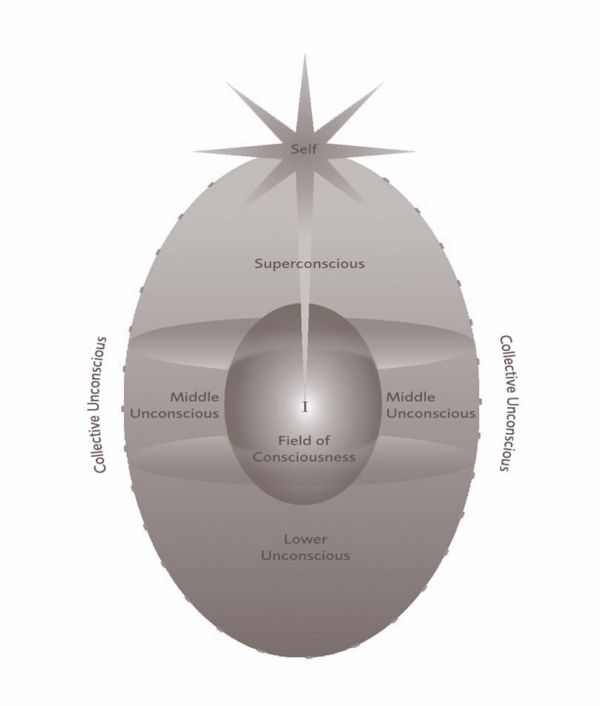

During this phase of his intellectual unfolding Assagioli also became acquainted with Freudian psychoanalysis, however, as history would reveal, this relationship was rather superficial and short-lived. In hindsight, the invisible strings envisioned by Freud to pull puppets and create the multiplex scenes of conscious life was for Assagioli merely a reductive yet essential prelude. When Assagioli finally submitted his doctoral dissertation to the University of Florence in 1910 under the title of ‘Psychosynthesis’, he highlighted what he perceived was conceptual short-sightedness on Freud’s part regarding the aetiological illumination of repression in psychopathology to the exclusion of all else; the overemphasis on ego development; and the erroneous inclination to pathologize the higher dimensions of the human personality responsible for spiritual emergencies like peak experiences, crises of transformation, and aesthetic experiences of oneness with nature and the cosmos. According to Assagioli, the immanence of the latter betrayed the existence of an inherent, universal pattern whereby all personalized, unified streams of consciousness move towards synthesis with a transcendental fount of spiritual energy called the Self. Once the warring subpersonalities within the psyche had been harmonized and a conscious, unified, and balanced centre free of dysfunctional handicaps had been developed (personal psychosynthesis), the Self came to the forefront and played a much more active, uninhibited role in unleashing the total sum of creative potential available to the healthy, uninflated ego (transpersonal psychosynthesis). Later, this transformational process was termed self-actualization by Maslow and recoined individuation by Jung. The intimate link between Assagioli’s clinical application of Maslow’s transpersonal theory is best illumined by the following short passage taken from the Textbook of Transpersonal Psychiatry and Psychology: “Whereas Maslow explored fundamental issues in transpersonal psychology, Roberto Assagioli pioneered the practical application of these concepts in psychotherapy. Assagioli proposed a transpersonal view of personality and discussed psychotherapy in terms of the synthesis of personality at both the personal and spiritual levels. He dealt with the issue of spiritual crisis and introduced many active therapeutic techniques for the development of a transcendental centre of personality.”

Contrary to exponents of reductive thinking, Assagioli was a man who felt as though each personalized stream of consciousness was a subjective singularity operating within an ambient relational and interactive field, one not be understood merely through a scrupulous scientific examination of its parts. He admits as such when he says: “Indeed, an isolated individual is a non-existent abstraction. In reality each individual is interwoven into an intricate network of vital, psychological and spiritual relations, involving mutual exchange and interactions with many other individuals.” Such a comprehensive view of human nature was always going to be at loggerheads with a Freudian drive theory unrelenting and unwilling to yield to other conceptual possibilities in its extreme point of view.

While Assagioli’s psychology was firmly entrenched and informed by Western approaches to psychotherapy, it remained ‘nondenominational’ by disidetifying from the deeply prejudiced outlooks to religion and spirituality that had typified the psychological traditions before it. As a holistic scientific discipline it appropriated empathic resonances to address both pathological and nonpathological experiences irrupting into psychological life; it aimed to facilitate psychospiritual growth and expansion within a clinical milieu most sensitive to personal aspirations, values, and life paths; and it wished to address fundamental questions of existence with utmost sensitivity to the ethnic, philosophical, and religious sentiments of the respective individual. By the same token its scientific grounding precluded it from adopting a particular standpoint on metaphysical realities and theological elucidations of the great cosmic mysteries. Not surprisingly, it remained tolerant of all theoretical and practical approaches to consciousness and personal development, excepting only the minimalist schools that did not acknowledge the spiritual experiences and meanings manifest in one’s life. With this newfound emphasis on personal growth, self-actualization, and the higher qualities and potentialities lying dormant like a kernel in the human psyche, Assagioli pioneered a rudimentary framework of clinical technique called psychosynthesis from which the ‘post-Freudian revolution’ of existential and transpersonal psychology could emerge and subsequently counteract the minimalist assessments of consciousness offered by behaviourism and psychoanalysis.